INTERVIEW: Vicki Thornton

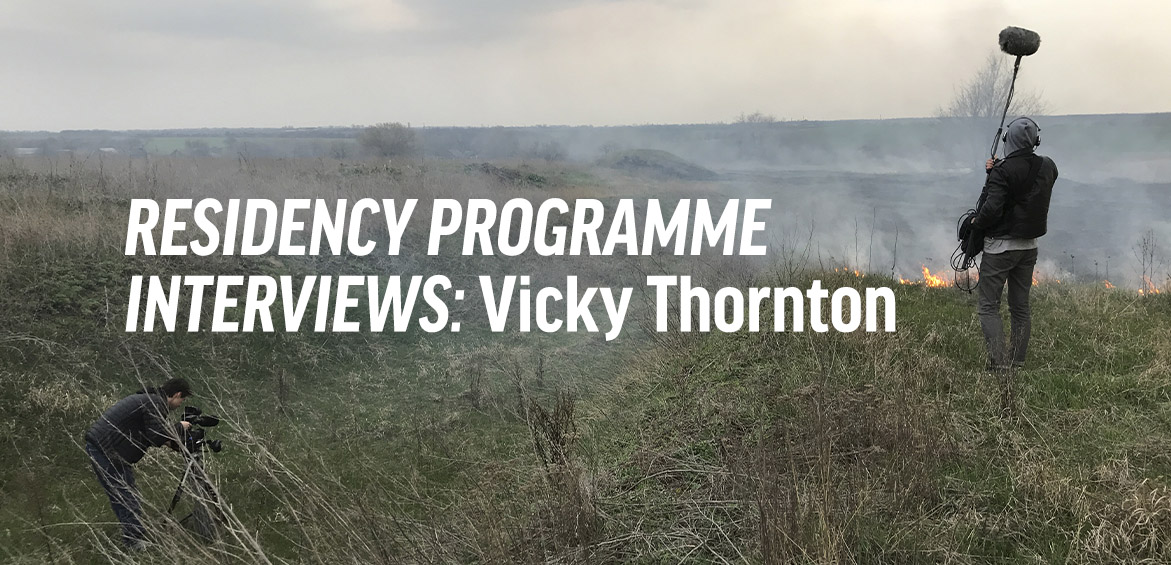

Photo: Filming in Donbas (photo Vicki Thornton)

Vicki Thornton is a British artist and filmmaker. She works in the field of visual art. Her work combines documentary and fiction filmmaking approaches to examine relationships between place, memory, performance and identity. Vicki was IZOLYATSIA resident during September and October 2017.

Please describe the general situation where you are. How are you? And how are your circumstances.

Vicki: I’m back in London now after spending just over two months in lockdown in a small village in Derbyshire. Things have eased up a bit here in the UK (we are able to meet up to six people outdoors now) but it still feels like a very strange time as our figures are not going down much at all. It has been a pretty terrible time in the UK overall — most people I know are out of work and there is little financial support for freelance artists and creatives. There is a lot of anger here about how incredibly badly the pandemic has been handled by our government. And of course quite rightly there is an incredible amount of anger about the brutal murder of George Floyd and what that represents here in the UK.

What was the project that you developed during your residency at IZO? It’s been quite a long time since your residency. Are you continuing this project? What has happened to it? How has it evolved?

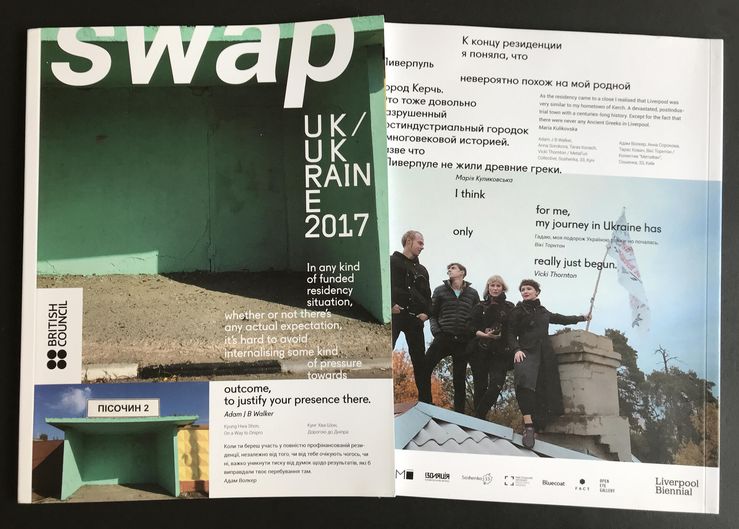

Vicki: I was artist in residence at IZO in Autumn 2017 as part of the British Council’s SWAP UK/Ukraine programme but I’d already spent a bit of time in Kyiv since I was also part of the DocWorks UA/UK programme run by Sheffield Doc/Fest and Docudays International Human Rights Documentary Film Festival between 2016-2017.

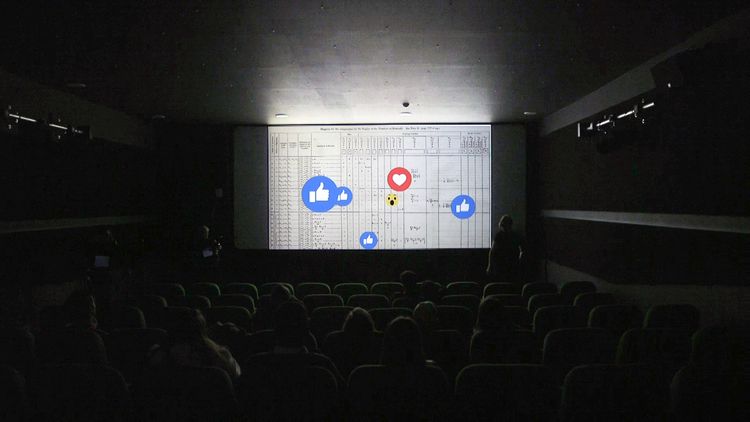

The main projects that I developed during my residency were TOMBOLA!, a participatory live performance event which later turned into a video installation with my now-frequent collaborator (!), Adam J B Walker, and a series of group Crits that the two of us set up with Anna Sorokovaya and Taras Kovach at the National Academy (НАОМА) and Soshenko 33.

Not long after the residency I also began shooting a documentary film / theater collaboration with Pavlo Yurov about the coal mining communities of Western Donbas so I have spent a lot more time travelling back to Ukraine over the last few years.

And I also returned with Adam J B Walker in late 2019 with the support of i-Portunus to work on STATESCAPE∞, a documentary research / game project about Mezhyhirya, the former home of deposed President Victor Yanukovych.

What were the rewarding and/or redeeming aspects of your residency at IZO? How did the residency support/influence your project/practice?

Vicki: I think the most important thing for me was the opportunity to be able to spend an extended period of time in Kyiv and to explore lots of places that I hadn’t been before (before this I had only ever come for a week at the most) — places like EFIR, Plivka, the Troeschina district — and also making links with younger Ukrainian artists as a by-product of the Crits. This really changed my approach to making and I’m now very connected to ideas around collaborative practice. And IZOLYATSIA as an institution has been very supportive of my work — particularly Oksana, Clemens and Lina — I’ve stayed in the residency accommodation many times over the last few years and keep in close contact with many of my friends in Kyiv.

Can you tell us the most memorable story from your time in residence or any interesting discovery you’ve made?

Vicki: I suppose putting on TOMBOLA! was pretty memorable, covering the whole of the ground floor at IZONE with kilos of gold glitter (metafan)! And everything that happened since — spending all that time in Donbas was really an amazing adventure!

How does the global pandemic influence your artistic practice\professional life and the project you developed at IZO in particular?

Vicki: Thanks to the support of House of Europe, I was actually due to be back in Ukraine in March 2020 to start the final phase of our mining project but of course I wasn’t able to travel in the end. But Pasha and I have spent a lot of time during lockdown speaking on Skype and developing our project remotely — we also participated in the recent Hatathon and met some great theater and film contacts there which was super inspiring! But of course, like everyone, the pandemic has affected my life hugely. I teach film practice and photography here in London and all of that work has transitioned to online which has not been easy to do with a six year old at home with me all day!

But I have truly been amazed at the quality of films and artworks being produced by these students during lockdown: they are all in different places — in China, Singapore, some in the US, Hungary, Switzerland, Ibiza and the UK — and all living in very different conditions but they all making incredible, thoughtful, personal and challenging works. I think that these spaces of mutual support and understanding that can be created online — such as this one and the one I have with my collaboration with Pasha — are really a lifeline during these difficult times.

I’d really like to see this feeling of generosity and sharing continue more widely beyond this moment throughout the creative industries. I think that the culture of competition within the arts is something we should all gladly leave behind after all of this!

Does this situation impact your artistic views or conceptual or aesthetical ideas that you can express through your practice? How?

Vicki: I think I answered this above but, yes, it changes my views on the way I want to live my life and what are the really important things to me. I don’t want to make work to someone else’s set of rules and I want to surround myself with inspiring, open and kind people. I think this pandemic should be a wake up call for everyone — to slow down, to reconsider the speed in which we have all been living, to spend more time with the people we love and to fight for the rights of those who can’t.