INTERVIEW: Juliette Déjoué

Juliette Déjoué is a French artist, her practice is mostly painting but it is also connected with the theater. She reflects and reconsiders space, objects and people, who usually turn into characters — they are more than human figures but something that is related to fiction in her works. Juliette likes the idea of confusion and borders fading away, eventually vanishing.

Please describe the general situation where you are. How are you? And how are your circumstances.

I’m in Casablanca, Morocco right now and I’ve been here ever since marsh 6th. I came for a week long event and because of the pandemic I was never able to leave. The event was cancelled and here I am. Almost three months now. Here lock down lasts until 10th of June. I hope I can go home shortly after.

What was the project that you developed during your residency at IZO? It’s been quite a long time since your residency. Are you continuing this project? What has happened to it? How has it evolved?

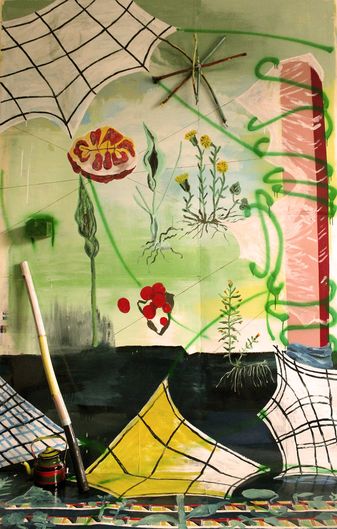

My project in IZO concerned popular culture. I was influenced both by local folk art and old soviet items I found at Potchaina flea market. I was trying to find something that would grasp all of it, maybe was I looking for a color pattern. The result was mostly painting, but I also experimented working with objects and I made a set in order to take pictures of people in it, or have people take pictures of themselves. We did a few tests with the Izolyatsia team.

While working, I realized how political any image can be (even the less political at first sight). I had very interesting talks with different people and understood several things about the actual situation in Ukraine. (Mostly concerning the new 2014 laws that supervise how communist related images should or should not be shown. My quest put me in the middle of the debate. I made things that I thought were innocent and ended up upsetting people.)

In many ways the whole project is a never ending one. The concerns I had in Ukraine follow me wherever I go. I have never really stopped working on it.

What were the rewarding and/or redeeming aspects of your residency at IZO? How did the residency support/influence your project/practice?

I think in some way, confronting myself to recent history through my work and my investigations was very important both for my global knowledge and for my personal work. It helped me to understand how anything we do is connected to politics. I’m more aware of the strong bond that links me to society.

The artist is not only a witness, through his work he can influence eyesight and maybe create a deeper understanding of the complexity of a situation. And being somehow on the edge, he has a distance others don’t necessarily have.

It’s a thought. I hope to achieve that though.

I was also very glad to discover Ukraine (although I know there’s more to see than Kyiv), and I can’t wait to come back. Hoping the event won’t be postponed again…

Can you tell us the most memorable story from your time in residence or any interesting discovery you’ve made?

Potchaina [flea market] was a great discovery for me, I was there every weekend or so. Flea markets very often give me the feeling I’m in some kind of outdoor museum. There is a strong aesthetic. Being interested in the past as well as in popular cultures, there is something that moves me a lot in the way old artefacts lay on the ground often surrounded by others that have nothing to do with it. And the person who displays them usually chooses how to show them. In my opinion, this choice is already art. In a humble way. I like humility in art.

The soviet art museum [Juliet is talking about a museum in Kmytiv] A museum that was in the countryside outside Kyiv and that displayed all together soviet art and contemporary ukrainian art. The purpose (as I understood) was to overcome the fight around what can be shown or not by creating a dialogue between two periods of time. (the idea being to promote freedom?)

It was interesting for me to see my little struggle expressed on a way larger scale among Ukrainian artists.

And the forgotten zone behind the train rails near Izone. It was like going through the mirror to fish new items and ideas. Thank you to Mathilde for showing it to me. One of the things I liked about it was that there were obstacles. Wild dogs on the way. And the access was this little hole in the wall you had to get through without anybody noticing. It was dreamlike. And sometimes scary.

How does the global pandemic influence your artistic practice\professional life and the project you developed at IZO in particular?

This period gave me the opportunity to realize how important other people are for my artistic reflexion and for my global understanding of the world. It really strikes me. I long for my people.

On another hand, it also helped me to acknowledge something about how I work: I need very little. As I said earlier I came with almost no materials (pencils, a needle and some thread). I ended up using anything I found: pieces of fabric, threads, pieces of wood, etc. Anything.

I have been drawing a lot, and the Kyiv project is always on my mind, I have also been working on costumes to go with my painted set.

I think artists are lucky to be able to always carry their practice with them. I feel lucky. It helped me keep some kind of balance.

Does this situation impact your artistic views or conceptual or aesthetical ideas that you can express through your practice? How?

The whole situation gave me the very strong feeling artists couldn’t be only witnesses of history and had to take an active part in anything happening. Not only the pandemic but also it’s consequences (the social ones + the dream lots of us had that a change would come)

I want to take part.