ZMINA: Rebuilding | Ukrainian Films as Testimonies of War in Helsinki and Vilnius

Helsinki and Vilnius, two European capitals, have become home to the Ukrainian Film Days. The documentaries and feature films presented at the festival brought with them the reality of war, the power of culture, and the ability to build bridges between nations. We spoke with Nataliya Teramae, the organizer of the Helsinki festival, who also answered on behalf of Anna Burdina, the organizer of the festival in Vilnius, about both parts of the event held in these two different cities.

First, can you please introduce the Ukrainian Film Days festival, its history, and the initial motivation behind its creation?

It is an annual festival that started in 2017 and aims to present Ukrainian culture and history through the best examples of both modern and classic Ukrainian films. The idea for the festival emerged in 2016 when Oleg Sentsov’s film Gamer was screened at a Russian film festival in Helsinki. At that time, Sentsov was a political prisoner of the Kremlin, and the need to make our voices heard was evident. I believe that cinema is one of the most effective tools of cultural diplomacy. Ukrainian Film Days in Helsinki is the only annual festival dedicated to Ukrainian cinema, and until recently, it was the only event representing Ukrainian culture in general. In 2023, we introduced a multidisciplinary festival called #UkraineSeason.

I believe that cinema is one of the most effective tools of cultural diplomacy.

Nataliya Teramae, the organizer of the Helsinki festival

My colleague, Anna Burdina, who relocated to Lithuania after Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine, had been working on a similar project in Vilnius. In 2024, we decided to join forces in cultural diplomacy and created a Finnish-Lithuanian project—Ukrainian Film Days in Helsinki and Vilnius.

How was the most recent edition of the festival different from previous ones?

Each year, we choose a central theme and adapt the programme according to the needs of our audience and external challenges. For example, this year, we focused on the topic of women in wartime—a subject that resonates with both Ukrainians and Finns.

Nataliya Teramae, the organizer of the Helsinki festival

Shared themes serve as a powerful bridge for mutual understanding. By highlighting the experiences of women during war, we aimed to shed light on the challenges faced by Ukrainian women in various roles—both as civilians and as military personnel. To explore this topic further, we invited key researchers and opinion leaders, such as Mariia Berlinska, director of the Aerial Reconnaissance Support Centre, and Tamara Martsenyuk, an associate professor at the National University of Kyiv-Mohyla Academy.

In Vilnius, Anna Burdina curated a diverse selection of Ukrainian films, facilitated connections between Ukrainian and local filmmakers, and organised an important discussion entitled Ukrainian Visual Culture: Rebuilding.

What criteria did you use to select the films included in this year's program? Did you adjust the curatorial approach in response to the ongoing war in Ukraine?

We select films that have either received critical acclaim or awards at international festivals, are recognised as cinematic classics, or effectively explore important topics.

Since the festival’s inception, we have consistently aimed to highlight Russia’s war against Ukraine in some way. Russia’s aggression is not merely a regional conflict—it is part of a larger global struggle. Therefore, we could not ignore the war, as it remains the most significant threat to European security today.

Can you share more details about the theme chosen for this edition?

This year, Ukrainian Film Days in Helsinki focused on women and their various social roles during the war. In Ukraine, almost 70,000 women serve in the Armed Forces, with approximately 4,000 on the front lines (Ministry of Defence of Ukraine, summer 2024). Many women are actively engaged in volunteer work, while others have left the country to protect their children. As of July 31, 2024, there are 64,415 Ukrainian refugees in Finland (UNHCR).

Alongside four Ukrainian films, we screened a Finnish documentary to discuss the impact of World War II on Finnish society. A crucial point raised during the discussion was the role of information warfare as part of conventional warfare—a strategy used by the Soviet Union in the past and now employed by Russia in the present.

Who was involved in organizing the festival?

In Helsinki, we collaborated once again with the Oleksandr Dovzhenko National Centre (Ukraine) and the National Audiovisual Institute (Finland), both of which are responsible for preserving national cinema heritage. In Vilnius, our partner was the renowned Skalvija Cinema Center. Engaging experts from these institutions was essential in organizing the festival successfully.

Approximately how many people worked on the festival?

In Helsinki, there were approximately nine team members, including volunteers. Additionally, in Vilnius, there were four team members, also including volunteers.

How much interest does the festival attract? Do you have an estimate of the number of visitors?

We successfully organised and carried out film screenings and discussions in Helsinki and Vilnius, engaging over 1,100 attendees, including stakeholders, public sector employees, and film industry professionals.

Nataliya Teramae, the organizer of the Helsinki festival

Although attendance fell short of our initial target of 1,800 participants, the high level of engagement and the impact of the discussions reinforced the importance of such cultural initiatives.

What kind of feedback did you receive from the audience?

This was the eighth edition of the festival in Helsinki, meaning we have built up a strong reputation and a dedicated audience. As a result, the feedback was overwhelmingly positive. Finnish audiences are eager to gain access to Ukrainian films and interact with Ukrainian artists, as it offers them a unique opportunity to discover Ukraine. For Ukrainians, the festival provides a sense of home—they miss their country and its cultural environment. Both audiences expressed a desire for an extended programme with more film screenings.

How much attention did the festival receive from local media?

Ukrainian culture is still not widely understood or appreciated by Finnish media, which is why I have always placed significant emphasis on promoting the festival locally. In 2024, the festival was covered by online and print media as well as television. I particularly appreciate that, year after year, the festival is highlighted by Finland’s largest newspaper, Helsingin Sanomat. In Vilnius, the festival also received strong media coverage, including features in major national outlets such as LRT and 15min.

Could you introduce the selected films in more detail and explain why they were chosen for the program?

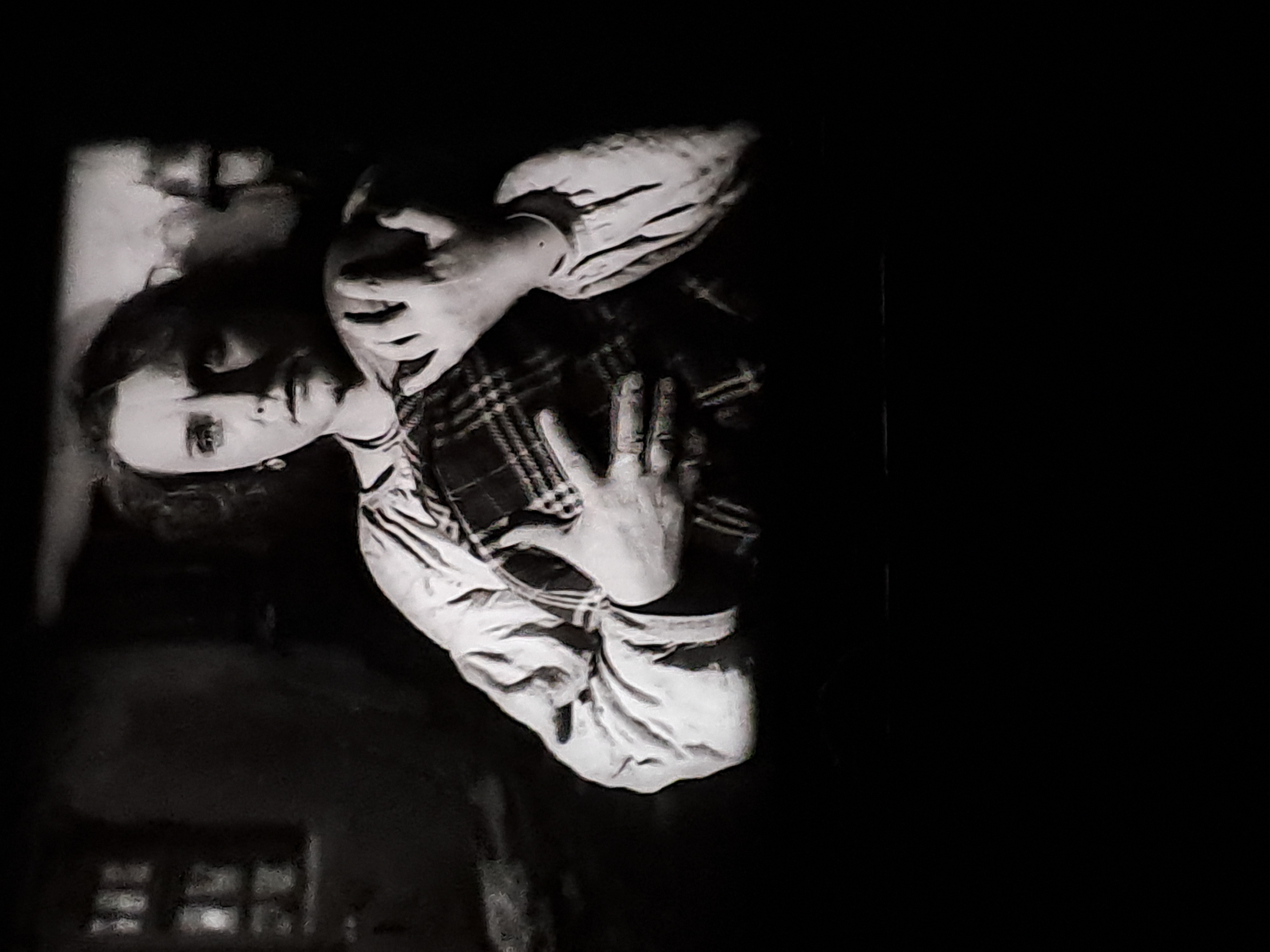

The Finnish documentary Lotat / Women at War was filmed in 1995 by female director Taru Mäkelä for the national broadcaster YLE. At that time, Finns were rediscovering their modern history, which had been heavily censored by Moscow. The film tells the story of the dedicated service of female volunteers from the paramilitary organisation Lotta Svärd and how the Soviet Union sought to discredit their work.

I would also like to highlight the Ukrainian documentary Invisible Battalion (2017), which was the first cinematic attempt to address the role of women in the military. The film was part of a major advocacy campaign and is available for free online.

Rock. Paper. Grenade is the feature-length debut of acclaimed Ukrainian film director Iryna Tsilyk. It tells the story of the relationship between a boy named Tymophii and his new family member, Felix—a veteran of the Afghan war suffering from PTSD.

What impact does the festival have on the Ukrainian community living abroad?

As I mentioned earlier, the festival gives Ukrainians a sense of home. Moreover, it allows them to witness the evolution of Ukrainian cinema and changing artistic trends.

Knowing that our culture remains alive sends a powerful message: we will survive, no matter what.

Nataliya Teramae, the organizer of the Helsinki festival

Do you have an estimate of whether more foreigners or local Finns attend the festival?

Primarily Finns. However, the festival also attracts international attendees, including students, diplomats, and local expatriates.

Have you noticed significant changes in Ukrainian films over the past few years due to the ongoing war?

Yes. Naturally, the main focus on is the war. Documentaries have become a major trend again, much like in 2014 during the Revolution of Dignity. The success of 20 Days in Mariupol and Porcelain War is a testament to this. Additionally, filmmakers—especially young ones—have started exploring the 1990s, a particularly difficult period for Ukrainians. I believe this is their way of processing the ongoing war—by examining past societal phenomena to better understand present challenges.

What was the biggest challenge in organizing this year's Ukrainian Film Days?

For a long time, securing financial support was the biggest challenge. Fortunately, we were selected for the #ZMINA_Rebuilding programme, created with the support of the European Union. This initiative was launched under a dedicated call for proposals to support displaced Ukrainians and the Ukrainian cultural and creative sectors, with backing from IZOLYATSIA. Platform for Cultural Initiatives, Trans Europe Halles, and Malý Berlín.

What are the festival's plans for the future?

Unfortunately—or perhaps fortunately—we can't screen all the films we'd like to, as there is an abundance of high-quality productions in Ukraine. That said, we already have ideas for the next festival. We are currently considering two potential themes: Transit 1990s or 10 Years of War: Films and Trends.

Nataliya Teramae, the organizer of the Helsinki festival

What emotions or thoughts would you like people to leave the screenings with?

I want to spark their curiosity and encourage critical thinking.

Author: Ján Janočko

ZMINA: Rebuilding is a project co-funded by the EU Creative Europe Programme under a dedicated call for proposals to support Ukrainian displaced people and the Ukrainian Cultural and Creative Sectors. The project is a cooperation between IZOLYATSIA (UA), Trans Europe Halles (SE) and Malý Berlín (SK).