ZMINA: Rebuilding | The Language of Silence: Ukraine’s Cultural Resistance at Malta Biennale

The screen shows a quiet port city—Berdiansk, now under Russian occupation. There was no voiceover. Just the sound of wind and water, the empty creaking of abandoned piers, and the slow rhythm of waves against concrete. It’s a haunting kind of silence—the kind that suggests something has been taken, and nothing has yet returned.

A few hundred metres away, sunlight cut through the heavy stone of the Grand Master’s Palace in Valletta. The building, once a symbol of colonial power in the Mediterranean, was now hosting the first-ever Maltese Art Biennale. And among its opulent halls and imperial corridors, the Ukrainian pavilion whispered a different kind of story.

Curated by Kateryna Semenyuk and Oksana Dovgopolova, Memory Unveiled was more than just an exhibition. It was an act of quiet resistance. In a war where noise dominates—bombs, speeches, slogans—Ukraine’s artists chose to speak through absence, fragility, and care.

There, memory became protest, and art became the silence that speaks.

Ukraine and Malta: Two “Invisible” Colonies

On the surface, Ukraine and Malta may seem worlds apart—geographically, culturally, politically. Yet both countries share a complex relationship with imperial histories. Long ruled by foreign powers from the Knights of St John to the British Empire, Malta is no stranger to being cast in the role of a strategic outpost. Ukraine, likewise, has endured centuries of domination—from the Russian Empire to the Soviet Union—and continues to resist attempts at erasure today, with Russia on its borders.

For curators Kateryna Semenyuk and Oksana Dovgopolova, presenting Ukraine’s pavilion inside the Grand Master’s Palace in Valletta carried a layered symbolism. The space itself, once a bastion of imperial and colonial power, stood in contrast to the topics of memory, absence, and vulnerability explored in the exhibition. No one sought to neutralise the building’s history; rather, they allowed the artworks to exist in dialogue with it.

The Ukrainian pavilion deliberately avoided grand gestures. In the ornate halls of the palace, it spoke in quiet tones—subtle installations, silences, and shadows. That restraint was a conscious gesture, echoing the fragility and resistance that define much of Ukraine’s cultural experience. Having reclaimed space traditionally used to assert dominance, the pavilion invited the viewer to reflect not only on the legacy of empires, but on the persistence of those who were meant to be forgotten.

Why the Mediterranean Perspective Matters

The 2024 Malta Biennale was framed by a curatorial concept titled “white sea olive groves,” evoking the Mediterranean as a space of layered histories, fruitful exchanges—and enduring conflicts. For the Ukrainian curators, the idea of exhibiting in the heart of this sea was not only about geography. It was about conversation, with the sea as a connecting space. On European maps, the Mediterranean often appears as an edge—a southern border where the continent seems to dissolve into sea. But from within, it lives as something else entirely: a gravitational centre, a meeting point of histories, a place where empires have collided and coexisted, where silence and memory ripple beneath the surface. Malta, an island nestled in this sea, remembers these tides—its colonial past, its strategic occupation, its quiet resilience. And from here, Ukraine’s curators chose to speak—not about Russia, but about the Black Sea.

“Odesa and Crimea are the spots where the Mediterranean meets Ukraine,” says Oksana Dovgopolova. This point of contact became the conceptual anchor of the pavilion. By turning southward, the curators resisted the habitual framing of Ukraine through its entanglement with Russia. Instead, they proposed a different geography—one that places Ukraine within a broader, interconnected history of empire, resistance, and transformation.

The Mediterranean perspective is not just geographical—it’s epistemological. It allows Ukraine to see itself not as a perpetual victim of aggression, but as a cultural agent with its own stories to tell. “We, as Ukrainians, can also look at ourselves from the other perspective,” Dovgopolova noted. Through this shift, silence emerged not as an absence, but as a presence—a deliberate, resonant quiet that does not disappear.

What Ukraine Brought to the European Table

At the heart of the Ukrainian Pavilion was a curatorial choice that resisted the logic of spectacle. There were no walls saturated with imagery of war, no aggressive symbols, no soundtracks of destruction. Instead, visitors stepped into a hushed architecture—spare, deliberate, attentive. There, war was not shouted; it was held.

Rather than commissioning new works designed to perform grief, the curators selected existing pieces by Ukrainian artists whose practices already engage with memory, absence, and fragility. These were not artworks made for the war—but through its lens, they speak differently now. Their meanings have shifted, acquiring new layers through proximity to loss, resistance, and historical rupture.

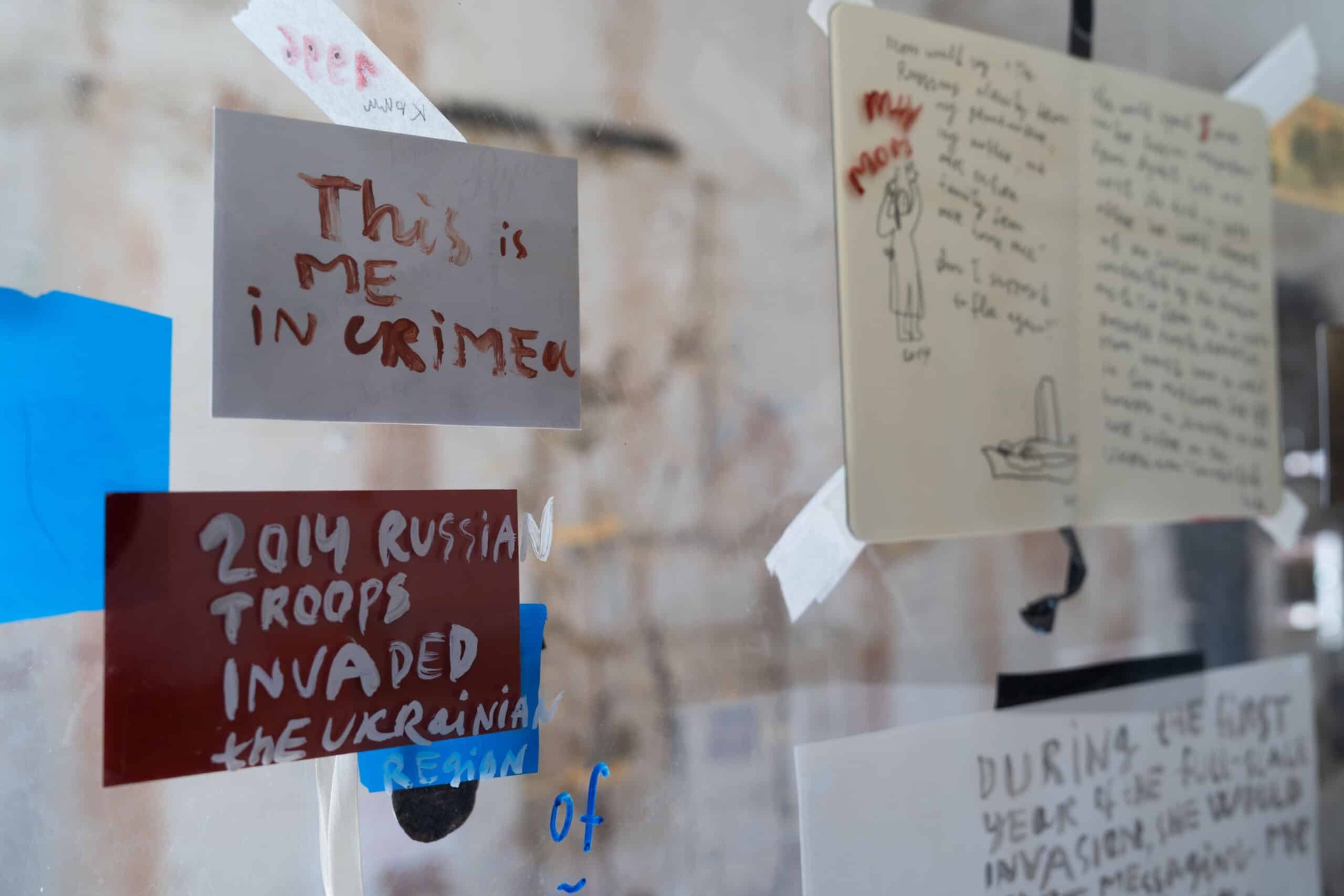

Alevtina Kakhidze’s happening, From Malta to Yalta, braided personal history with imperial critique, inviting the audience into a live moment of reflection. More than 50 people took part. “The first impressions and feedback were very positive,” noted Kateryna Semenyuk, recalling the intensity of the pre-opening days. The pavilion drew curators and cultural stakeholders from Spain, Italy, Poland, Denmark, the Netherlands, the UK, Germany. “After the Ukrainian pavilion opening on March 14, we felt there was a big interest from diverse stakeholders.”

This wasn’t just about showing Ukraine—it was about reimagining how war and identity could be communicated in the European art space. The curators moved away from showcasing trauma through shock, instead creating a space where silence, restraint, and openness invite reflection. The absence of noise became an ethic of care.

The decision to work with already existing artworks was also shaped by necessity—limited funding and a tight timelines—but it became a method.

“ZMINA Rebuilding was the only funding opportunity we applied for, as we knew we were 100% fit as a project,”

explained Semenyuk.

Within those constraints, the curators found precision. The artworks were not overwhelmed by explanation—they were allowed to breathe, to resonate. By choosing care over spectacle, the Ukrainian Pavilion asked not for pity, but for presence.

Reconstructing Identity Through Art

For Semenyuk and Dovgopolova, the Maltese pavilion was not a standalone effort, but part of a longer, deliberate conversation with memory. As co-founders of the Past / Future / Art platform, they have long worked at the intersection of history, trauma, and collective reflection. Their previous projects, such as Mariupol Memory Lab, were about building the conditions for remembering differently.

The Maltese pavilion continued this trajectory, being a space of soft insistence. The curation was spare, almost minimal—by design. Visitors entered not to consume information, but to slow down, to feel. It’s the scale of the installation that mattered. It was intimate, but not closed; the silence was deliberate, not empty. For the curators, silence became a curatorial tool—a way to restore agency to both artists and audience. Fragility, in their approach, is not a weakness but a structure. It frames the experience and holds the viewer with quiet strength.

Art, in this context, became care. Alevtina Kakhidze’s live performance, the positioning of works, the absence of didactic signage—all of it constructed a space of trust. There were no answers offered. But there was a room where memory slowly returned—layered, uncertain, but present.

“Lost identities are the tragedy and the impact the empire has on Ukrainians,”

Dovgopolova reflects.

This pavilion didn’t seek to recover those identities with force. It simply opened a door—and waited.

Beyond Cancelling: Building New Narratives

The presence of Ukraine at the Malta Biennale was structural, shifting the logic of international art events from representation to resistance. The pavilion was not a reaction to someone else’s story; it was an act of authorship in its own right. A gesture of being that refuses erasure.

In curating the project, Semenyuk and Dovgopolova made an early and conscious decision: they would not centre their work around cancelling Russia. “We knew that Russia was not invited, so it was a relief that our task would not be again to cancel Russia,” Semenyuk explains. “We decided to offer our content, our context, our project and our perspective.”

The curators chose to work within the biennale’s national pavilion format—despite its colonial associations. Often criticised for mirroring the structure of the Venice Biennale, where nations are placed into symbolic competition, this model can easily reproduce outdated hierarchies. But for Semenyuk and Dovgopolova, it offered something else: a framework they could subvert from within. “Our project is about Ukraine and a new international cultural diplomacy platform which is built according to the principle of national pavilions,” Semenyuk says. Within that framework, they asked different questions—not only about how to be seen, but also about how to collaborate ethically.

The shift from decolonisation to co-creation runs through the core of the pavilion. It is not about replacing one empire with another or speaking over others, but rather about showing up—with care, with context, and with the full weight of history carried gently into the present.

A Quiet Act of Resistance

The Ukrainian Pavilion at the Malta Biennale didn’t overwhelm or perform grief. And in this restraint lies its force. In the ornate halls of the Grand Master’s Palace, Ukraine offered something quieter and more enduring. “The Maltese biennale helps us to get beyond canceling or boycotting Russia,” reflects Oksana Dovgopolova. “It helps us to get a new, independent perspective.” The pavilion resists not through confrontation, but by stepping out of inherited frames altogether.

Reluctant to define Ukraine in relation to its oppressor, they chose instead to speak in its own terms. “We want to change that,” Dovgopolova says.

“Why do we need to talk about Russia when we talk about Ukraine?”

Oksana Dovgopolova

Silence, here, becomes a method. A refusal to amplify the noise of violence. A language of care, precision, and continuity. “Ukraine helps Europe to get rid of ‘blind spots’,” she adds. In that sense, the pavilion is not only about remembering the past, but also a map toward another future—one where fragility is not weakness, and absence is not disappearance.

Where Empires End, New Maps Begin

Ukraine was participating in the Malta Biennale while under full-scale invasion, and that fact alone makes its presence extraordinary. But what the Ukrainian Pavilion accomplished goes further—it used culture not to escape war, but to speak from within it, carefully, deliberately, and with its own voice.

Malta Biennale 2024 was also a first. Organised under the patronage of UNESCO and the President of Malta, it reimagined what a biennale can be—especially in a region historically shaped by empire. “Malta is an invisible colony as much as Ukraine, in fact,” Oksana Dovgopolova notes. Both countries understand what it means to carry memory in silence, to exist between borders, and to reclaim space through narrative. “This resemblance appealed to us as curators right from the start, this change of perspective,” she continues. That shift—subtle, steady, structural—ran through the pavilion as a quiet contribution to a shared European future. “For Europe, it is an issue of survival,” Dovhopolova adds. “Europeans at large don’t see it yet. Ukraine can help.”

Changing perspective creates a new picture. The Malta Biennale may be just one frame—but it opens the way for different maps to be drawn.

Authors: Mariia Akhromieieva, Olga Zaporozhets

ZMINA: Rebuilding is a project co-funded by the EU Creative Europe Programme under a dedicated call for proposals to support Ukrainian displaced people and the Ukrainian Cultural and Creative Sectors. The project is a cooperation between IZOLYATSIA (UA), Trans Europe Halles (SE) and Malý Berlín (SK).