ZMINA: Rebuilding - Theater as a Shelter: Mariupol#nadiya_na_svitanok Brings Ukraine’s Reality to the World Stage

The Mariupol #nadiya_na_svitanok project uses theatre as both a reflection of Ukraine’s reality and a tool for healing. Co-authored by Maryna Bortnyk-Hulevata, head of the literary and dramaturgy department at the Khmelnytskyi Regional Academic Music and Drama Theatre, the play unfolds in the shelter of the Azovstal plant, immersing audiences in the psychological toll of war while focusing on resilience.

With its recent tour to Kraków and Barcelona, the performance has been raising global awareness and reconnecting displaced Ukrainians to their homeland. We spoke with Maryna Bortnyk-Hulevata about the challenges of staging such a production, the impact of cultural diplomacy, and how theatre can help shape Ukraine’s future.

How did the idea for the play Mariupol #nadiya_na_svitanok come about? What was the main impetus for its realisation, and which stages of the creative process were the most challenging? How did the war influence its concept and execution?

The idea for the play emerged at the beginning of Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine, during a time when many internally displaced people, including those from Mariupol, had found refuge in Khmelnytskyi. One of the co-authors, Maryna Pinchuk, is originally from Mariupol, and the tragedy of her hometown deeply affected her. She approached me with the idea of creating a work on this pressing topic.

However, the initial version of the play was highly tragic, and by the time we moved toward staging the production, it had undergone significant changes. We needed to give people hope!

Once the script was completed, I was able to secure a grant from the Ukrainian Cultural Foundation—a scholarship to continue my creative work—which provided the funding for the production of this art-therapy play. The project was brought to life by director Mykola Babyn, artist Diana Rudchuk, and choreographer Illia Shevchuk.

What were the main goals of the play’s tour? Was it primarily aimed at Ukrainians abroad, to inspire them to return, or at an international audience, to raise awareness of Ukrainian realities? How did the play balance these two objectives?

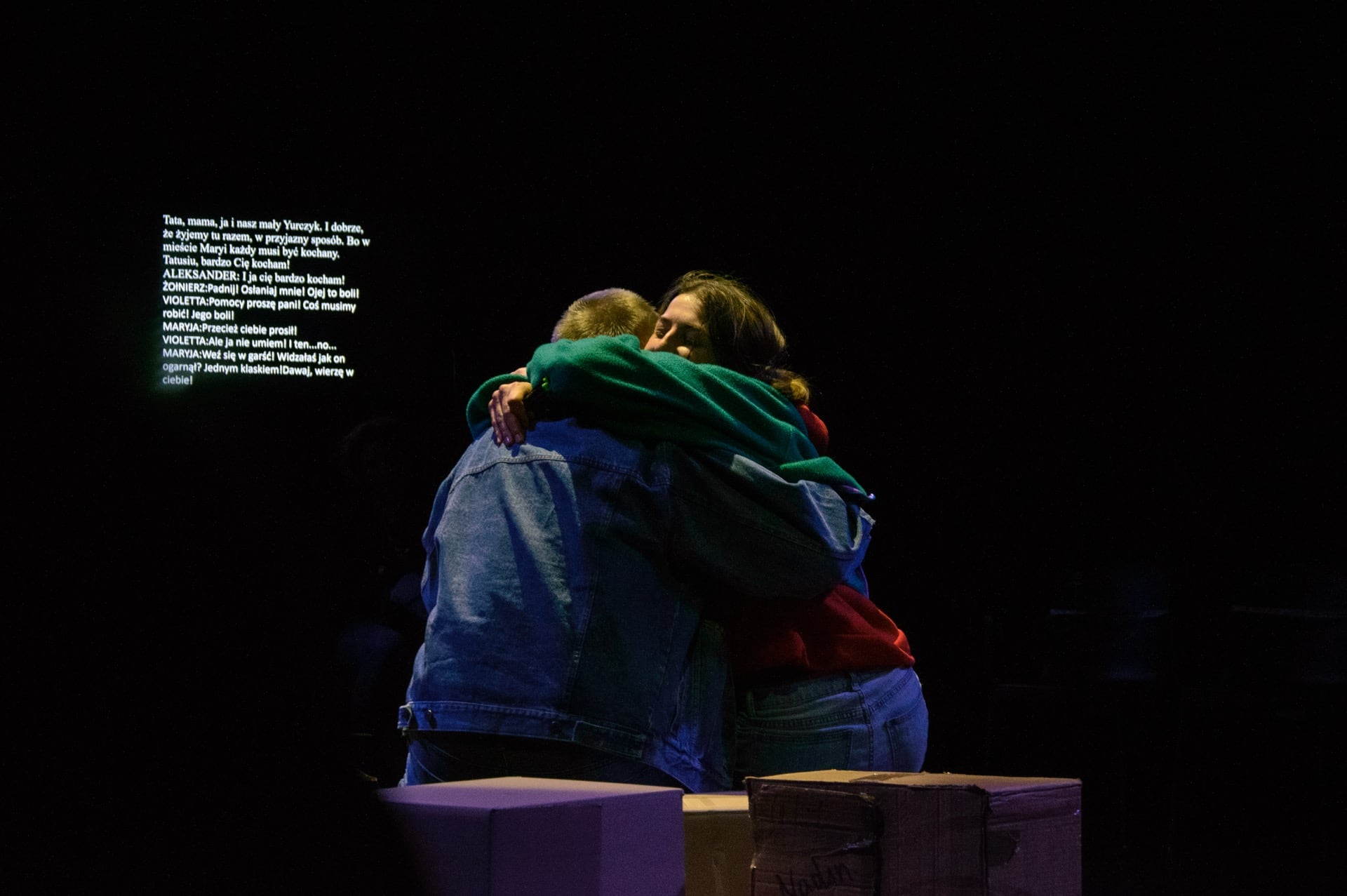

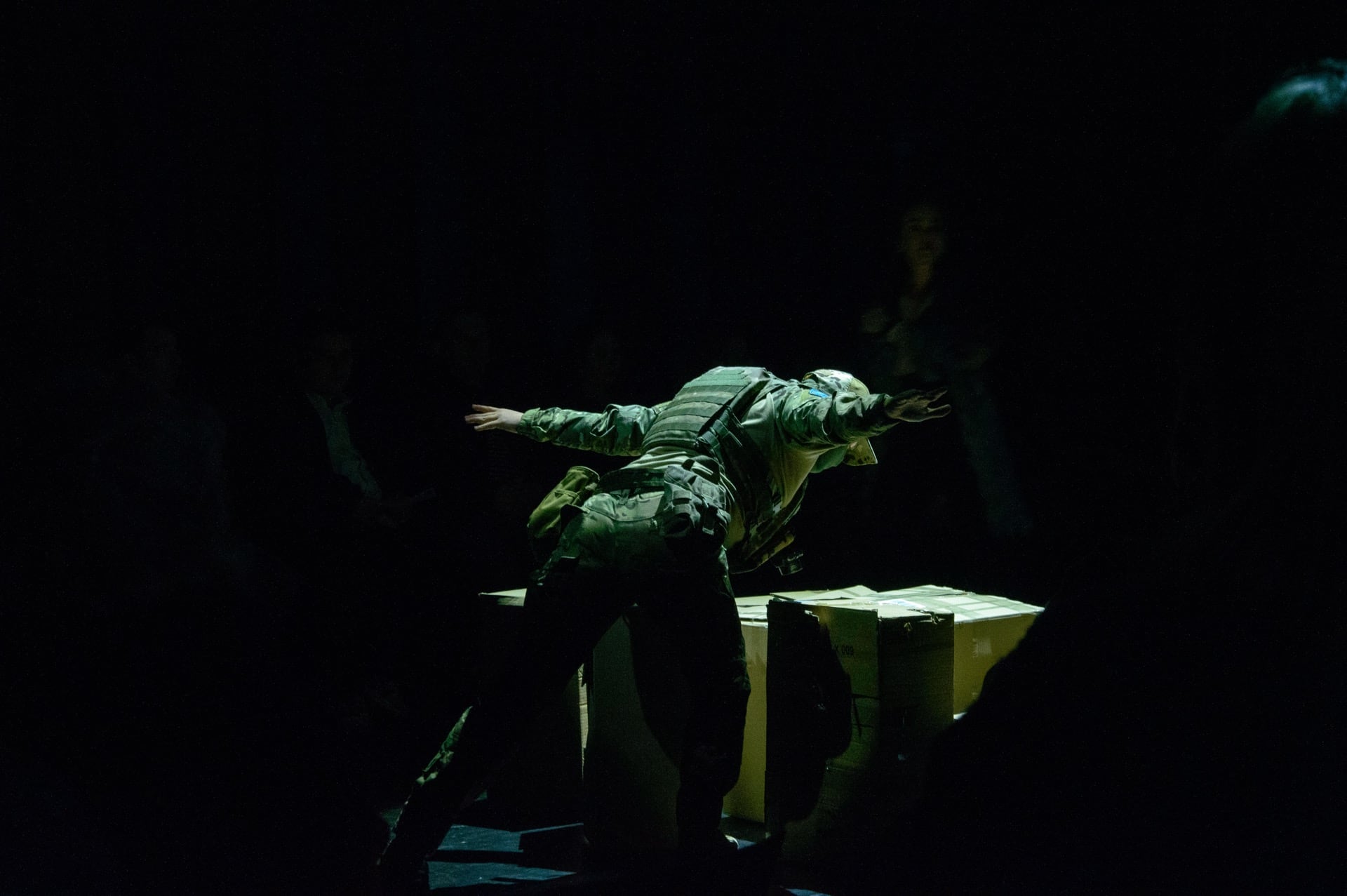

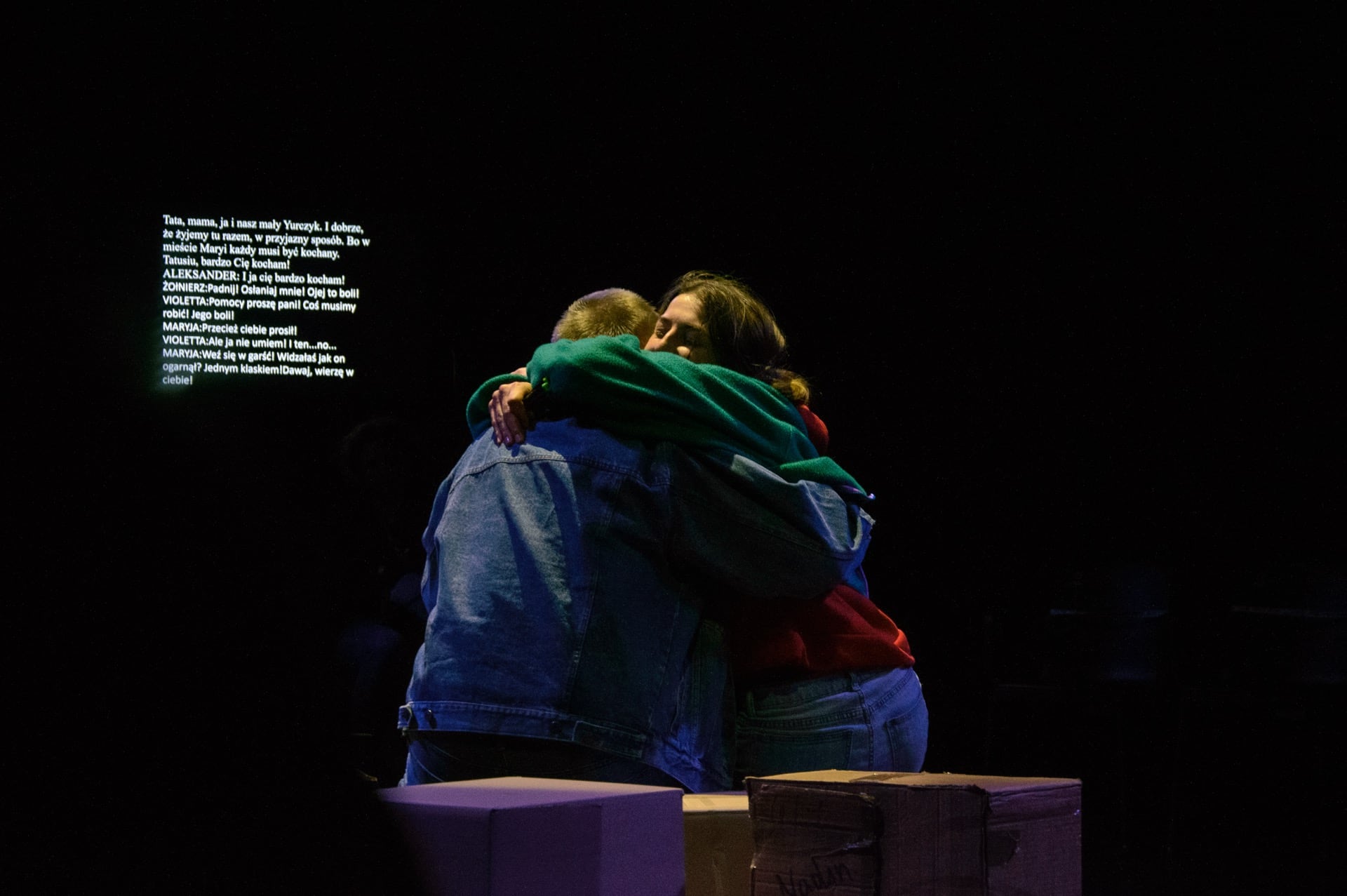

Of course, the tour was aimed at supporting Ukrainians forced to stay abroad. However, our primary goal was to show foreigners the reality of Ukraine. This play immerses the audiences in the harrowing experience of war—everything unfolds in the shelter of Azovstal, where spectators share the same space with the actors, becoming direct witnesses to the events.

Through this deeply immersive experience, we gave people in Spain and Poland a chance, even if just for two hours (the duration of the play), to feel what Ukrainians endured at the onset of the full-scale invasion and what they continue to endure today. By bringing together these two categories of viewers, we helped to bridge the emotional and psychological gap between them.

After all, not only those who remain in Ukraine need support and understanding—those who were forced to flee carry deep pain within them and also need to be heard. Ideally, everyone should live in their homeland, in their own home. But if Ukraine does not receive support now, if help does not come, millions of people will be left without a home at all.

Why was the story set in the shelter of the Azovstal plant chosen as the foundation of the play? What symbolism and deeper meaning does this place hold for both Ukrainian and international audiences?

The Azovstal shelter was where the horrors of this war truly began. It was a relatively safe refuge where thousands of Mariupol residents sought shelter—a place where fate brought together people of different backgrounds, statuses, and even political views. Yet, in the face of war, they had no choice but to survive together, side by side.

As I mentioned earlier, this setting is not just a metaphor. In Ukraine, we always perform the play in actual shelters—whether in the basement of the Khmelnytskyi Regional Academic Music and Drama Theatre or in the underground spaces of other theatres. During our tours in Kraków and Barcelona, we couldn’t use real bomb shelters (since such spaces are not yet part of daily life in peaceful countries). However, we requested stage venues that would recreate similar conditions—windowless, relatively small, with seating arranged in a circle. This setup allowed foreign audiences to experience what Ukrainians did at the start of the full-scale invasion: finding themselves face to face, forced to connect in an intimate, inescapable reality.

Beyond Azovstal, the play also commemorates other landmarks of Mariupol destroyed by Russia. One of the characters, Mariia—played by the honored artist of Ukraine, Larysa Kurmanova—is the oldest among them and serves as the keeper of the city’s history. As the events unfold, she recounts stories of Mariupol’s once-thriving buildings, bringing them to life even as they lie in ruins. To reinforce this connection, we brought photographs of these destroyed buildings to Poland and Spain, allowing audiences to see firsthand what the invaders had reduced them to.

Yet, amid the devastation, there is a moment of art therapy. The youngest characters, Viktoriia and Andriy (played by Anastasiia Boliukh and Dmytro Franchuk), invite the audience to bring colour to the gray shelter—to paint symbols of hope and dreams for the future. These artworks are then pinned onto the images of destroyed buildings, turning the ruins into a canvas of resilience. In Ukraine, we leave these paintings on the walls of the shelters where we perform.

The play combines art with elements of art therapy. How are these elements integrated into the storyline, and how do they affect the audience? Do you have any examples of their emotional impact?

Beyond being a place of physical refuge, bomb shelters are often bleak, damp, and claustrophobic, with little light or air. They are spaces that most strongly evoke the realities of war and the feeling of being trapped, both physically and emotionally. Ukrainians in these shelters often feel as if they are locked in a space with no escape, with no light of hope.

However, when the audience—together with the characters—are invited to colour this space, to add windows and brightness so they don’t miss "our dawn", it sends a powerful message. The play illustrates that while there are circumstances beyond our control, it is how we respond to them that matters. Even among ruins, it is possible to create a new city, a new life. The key is to have loved ones and a sense of togetherness.

One of the most profound indicators of the play’s impact is the audience’s reaction at the end—tears. But these are not tears of despair; they are tears of catharsis, of emotional release. Many people, since the start of the full-scale invasion, have built emotional armor around themselves, suppressing their pain in order to survive. However, for a wound to heal, it first needs to be cleansed.

During our tour, we conducted audience surveys to gather feedback on their impressions of the performance. It was deeply moving to see that the majority of responses were overwhelmingly positive, with many people expressing how much the experience resonated with them and helped them process their emotions.

Were psychologists or therapists involved in the preparation of the play to help shape its art-therapeutic aspects? How does the audience respond to these therapeutic moments during the performance?

Absolutely. Psychologists and psychotherapists provided consultations from the early stages of writing the play to the post-premiere discussions in Khmelnytskyi. Their input was instrumental in shaping the dramaturgical material, making it more positive and balanced.

While we couldn’t ignore the theme of death—since acknowledging emotions is essential to processing them—we carefully considered how to present it. Following the psychologists’ advice, we moved the moment of loss outside the stage space, beyond the shelter. Instead of directly depicting tragedy, the play focuses on how the characters cope with it. Through their journey, we show that even in times of grief and hardship, no one is truly alone. With strong faith and unwavering support, it is possible to endure.

Throughout the creative process, we were deeply concerned about ensuring that the play did not become a psychological trigger for the audience. That’s why we made every effort to navigate sensitive perceptions carefully.

The play emphasises the restoration of psychological and emotional well-being as a foundation for the future reconstruction of Ukrainian cities. In your opinion, how can cultural initiatives integrate into the process of physical and social rebuilding of the country?

Culture can serve as a form of soft diplomacy. Through theatre, audiences in other countries can connect emotionally with and better understand Ukraine’s struggles. These emotions are incomparable to simply knowing theoretical facts about events.

The elements of art therapy and the belief that everyone can contribute to change in their own way can inspire people to ask themselves: “How can I help rebuild someone else’s home?” or “How can I support those in need?”

Nowadays, not just thousands but millions of Ukrainians are scattered around the world. While coping with their own psychological trauma, they continue to fight for our country in the places where they have found refuge. It is crucial for them to know that they are not alone—that our shared pain is recognised and supported. And this support can come from people of other nations, regardless of status or position. Everyone, in their own way, can take at least a small step toward peace, freedom, and the rebuilding of Ukraine.

Do you have any stories from audience members who were inspired by the play? Were there cases where someone decided to return to Ukraine or join reconstruction initiatives after seeing the play?

The most powerful moments were the stories of audience members who, with tears in their eyes, thanked us after the performance. They said that amidst the everyday concerns—like deciding what coffee to drink—they had forgotten about the fundamental values of humanity and compassion.

We met residents of Mariupol who expressed their gratitude, saying, “Thank you for bringing us a piece of our life.” Foreign viewers, in turn, shared that Ukraine must continue to receive support and that they would stand by our country no matter what.

Why were Spain and Poland chosen for the start of the tour? Was this related to the large Ukrainian diaspora in these countries? What criteria guided your choice of locations?

In fact, even before the premiere in Khmelnytskyi, an organisation from Barcelona reached out to us, expressing a strong desire for us to bring the play there. Shortly after, Ukrainians from Kraków made a similar request.

Additionally, there is a direct flight from Kraków to Barcelona, which made logistics much more convenient. This tour naturally brought together both demand and opportunity.

Did you plan to engage the local audience in these countries during the tour? How was the play adapted for non-Ukrainian viewers?

In Spain, we had a simultaneous interpreter and the necessary equipment for live translation. In Poland, we used a screen with Polish subtitles, as the language is phonetically closer to Ukrainian, making subtitles the more convenient option for comprehension.

Over the past year, the Khmelnytskyi Regional Academic Music and Drama Theatre has actively operated under the difficult conditions of war. How has this affected your creative work? Have your priorities in repertoire selection or working methods changed?

The main changes related to working during the war involve constant adaptation to new challenges—both in meeting audience needs and in handling the physical conditions of our work. For example, performances must stop during air raid alerts, with everyone moving to shelters. After the all-clear, we either resume the play or reschedule it. However, Mariupol #nadiya_na_svitanok takes place in a shelter, so it can continue uninterrupted during air raids.

Thanks to the support of friends abroad, our theatre has also received a powerful generator, allowing us to work even during power outages—something that has been incredibly helpful in recent months.

As for audience preferences, the full-scale invasion has reinforced how essential theatre is for people. Both contemporary plays and classical productions of various genres and styles help audiences escape, recharge, and find relief from today’s harsh realities.

We also continue using theater as a form of art therapy. Recently, we completed another grant project with the Ukrainian Cultural Foundation—an art-therapeutic play for military personnel and war veterans, including those with disabilities. This production focuses on uplifting moments from difficult experiences, military humour, motivation, and gratitude for their service and sacrifice.

The theatre has many years of experience in creating productions across different genres. How has this experience helped in bringing such a complex and multifaceted project as Mariupol #nadiya_na_svitanok to life?

When speaking about experience, it is essential to consider history. Looking at the theater’s work during World War II, we see that the true power of the arts is in providing support and emotional and psychological relief to people enduring difficult circumstances.

The same holds true today—cultural workers cannot remain indifferent to critical events. Language and culture define our identity; they are the foundation of any nation. But they are also the inner nerve of every citizen. In times of hardship, culture must serve as a source of spiritual and moral support for all.

The theater’s international touring activity is an important aspect of cultural diplomacy. What lessons or experiences have you gained from these tours that could help in future work?

These were among the first international tours. In 2023, the theatre performed in Moldova as part of the country’s designation of 2023 as the Year of Ukrainian Culture. With this and previous experience, we can draw several conclusions.

The first is that cultural diplomacy is a powerful force that helps shape global perceptions of Ukraine. Such tours should be conducted on a regular basis to ensure that the world sees Ukraine as an independent country with its own history, nation, and traditions.

Additionally, the reception of our performances by international audiences confirmed the high quality of our work. This is crucial in overcoming the inferiority complex that the ideology of the aggressor country has tried to impose on us for years. Seeing that our productions are well received abroad motivates our team to grow, improve, and move forward.

Are you considering expanding the Mariupol #nadiya_na_svitanok tour to other countries? Have there been requests from Ukrainian communities or cultural institutions in other nations?

Yes, while organising this tour, we have received requests from Estonia and Germany. Naturally, we would love to bring the play to these countries. We are currently exploring financial opportunities to make such a tour possible and are in negotiations with representatives from these regions.

What key takeaways have you drawn from this project? Are there any ideas on how to expand the integration of art and art therapy into other theatrical initiatives in Ukraine?

Ukrainian theatres are now more united than ever. We constantly share experiences, maintain ongoing communication, participate in exchange tours, and organise festivals.

Before our tour in Spain and Poland, Mariupol #nadiya_na_svitanok was performed at a festival in Mykolaiv—in a theatre shelter—during a missile strike on the city. Right in the middle of the performance, an explosion occurred, and the lights went out. Part of the play was performed under the glow of audience members’ phone flashlights, and the rest continued with a generator.

This is the reality we all live in now. But this experience proves that there are no isolated initiatives anymore. We are all working toward a shared goal, experimenting in the same direction, supporting and helping one another.

10__resized.jpg)

In your opinion, how can art and culture be integrated into Ukraine’s long-term recovery strategy? What role does theatre play in this process?

Looking back at history, art, and culture have been among the first things invaders seek to destroy when occupying foreign territories. As mentioned earlier, they are the central nerve of any nation’s identity. Art and culture shape the ideology, worldview, and the spiritual essence of a people. Ukraine’s recovery is impossible without the development of these fundamental areas.

At the same time, during the war, national priorities are naturally focused on military needs, leaving culture and the arts in the most vulnerable position. However, this moment also presents a unique opportunity—doors are opening in many countries, offering their support and sharing their achievements with Ukrainian artists. This exchange will help to accumulate new knowledge, ultimately strengthening Ukraine’s long-term recovery with the renewed and powerful forces of theatre, among other cultural institutions.

Author: Mariia Akhromieieva

ZMINA: Rebuilding is a project co-funded by the EU Creative Europe Programme under a dedicated call for proposals to support Ukrainian displaced people and the Ukrainian Cultural and Creative Sectors. The project is a cooperation between IZOLYATSIA (UA), Trans Europe Halles (SE) and Malý Berlín (SK).