ZMINA: Rebuilding | Nature, Loss, and Reconstruction: Ukraine’s Presence at the Tbilisi Architecture Biennial

In 2024, the Tbilisi Architecture Biennial hosted a special Showcase Ukraine, which was made possible through support from the ZMINA: Rebuilding programme. The project intertwined several important themes: a strong ecological focus relevant to both countries—Georgia, with its policy of maximum resource utilization, and war-torn Ukraine; the issue of post-war reconstruction of houses and homes; and the challenge of coping with the traumas of aggression. How can architecture respond to such a broad spectrum of issues, ranging from the personal to the global?

In addition to the Biennial team, the preparation and implementation of Showcase Ukraine involved two Ukrainian partners: the urban laboratory MetaLab from the western Ukrainian city of Ivano-Frankivsk, and Kultura Medialna from Dnipro, an organization dedicated to contemporary art and culture, public spaces, and building urban communities.

We spoke with Tamara Janashia, project coordinator of the Tbilisi Biennial, and Anna Dobrova from Ukraine’s MetaLab, which she co-founded and currently leads, about the programme, the exhibitions, their thematic engagement, and the collaboration between the partners.

The connection between architecture, nature, and war

The Tbilisi Architecture Biennial (TAB) first appeared on the cultural scene in 2018. It combines a multidisciplinary approach to the themes it explores. Therefore, if you had attended last year’s edition, its fourth, you would have found not only exhibitions and lectures on architecture in the programme, but also art installations and film screenings.

The theme of this Biennial was Correct Mistakes. “I would say that this was kind of a wordplay. It wasn’t only about correcting mistakes—that’s why we deliberately didn’t phrase it that way. It was also about mistakes that, by their nature, could be ‘correct’,” Tamara explained. “This year, we had a very specific focus on the use of natural resources—how we seize them, how we exploit nature, the ecosystems, and how we often neglect the biographies tied to these environments.”

The theme began to take shape as early as 2023, when the organizers of TAB curated the Georgian Pavilion at the 18th Venice Architecture Biennale. Even then, they presented, for example, the Georgians’ resistance to the construction of dams and power plants that would irreversibly alter ecosystems and unique biotopes, a long and difficult path of protest and the situation in Georgia, which, as Tamara notes, often seeks to exploit its natural resources to the fullest, frequently for the benefit of foreign investors.

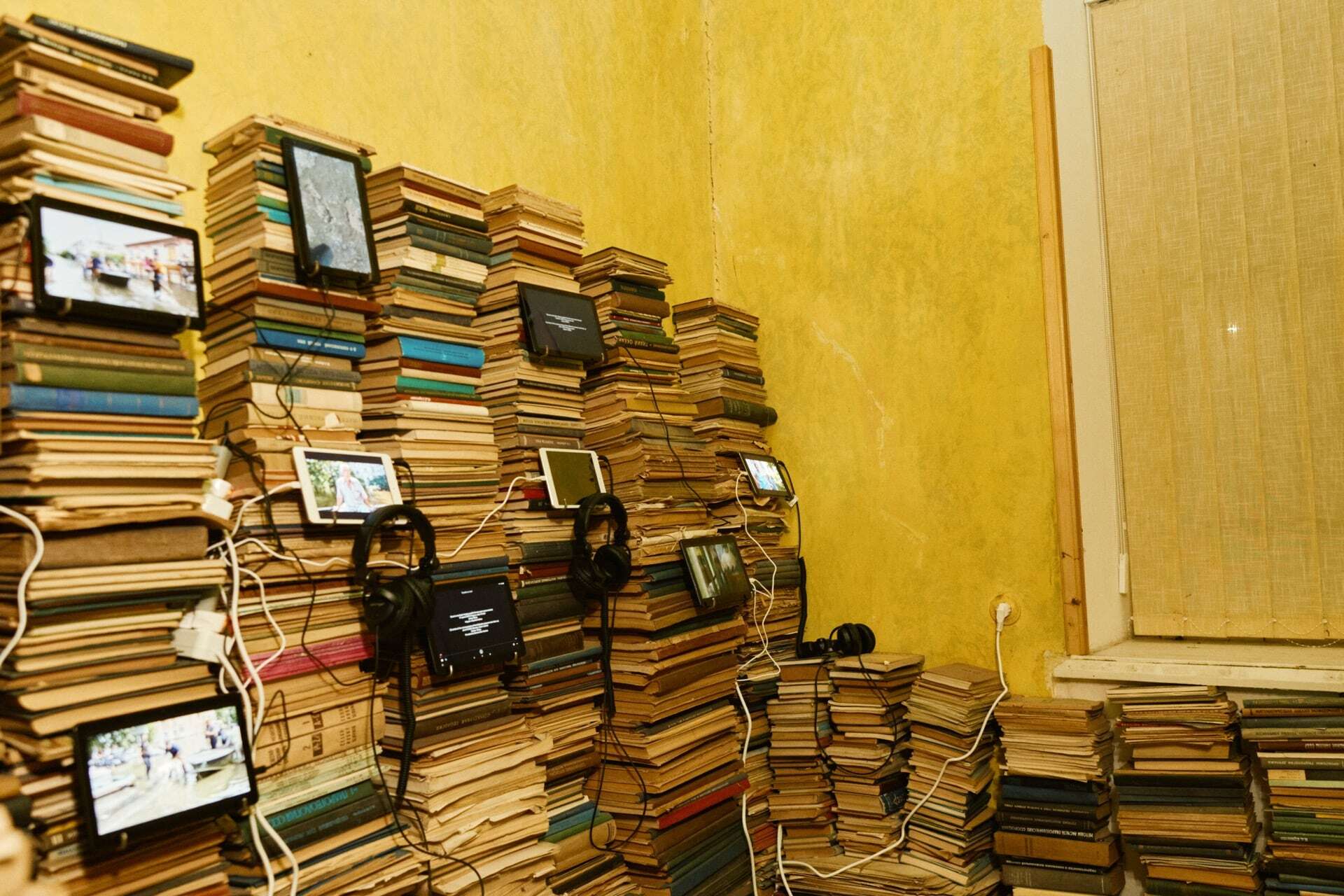

The issue of aggressive interventions into nature and human lives in strategic areas of the country, hydropower plants, forced displacement— these are not only Georgian concerns. Quite naturally, the TAB´s theme was followed by the exhibition The River Wailed Like a Wounded Beast, which was brought to the programme by the Ukrainian partner Kultura Medialna.

This organization, based in a city named after the Dnipro River, which once fed the Kakhovka Reservoir, explored the fate of this body of water in 2023 in collaboration with the Oleksandr Dovzhenko National Centre and Kyiv Biennial. The exhibition was shown in Kyiv and Dnipro, at the Berlin edition of the Kyiv Biennial (called Kyiv Perennial for its long duration ), and in Szczecin, Poland. The exhibition is a cinematic documentation of the dark side of Soviet modernization, the desire to dominate nature, and the spread of its ideology.

“This project addressed the tragedy of the Kakhovka Dam, which happened in June 2023 when Russian troops blew it up. This caused catastrophic results, flooding whole villages. It wasn’t only about the people, but it was also about security and environmental impact and impact on animals,” explained Tamara from the Tbilisi Architecture Biennale.

The Kakhovka Reservoir was located in the lower reaches of the Dnipro River, in the Kherson region. Although it was the second-largest reservoir in Ukraine by area, it ranked first in terms of volume, holding over 18 cubic kilometers of water. When the dam was destroyed, this water flooded approximately 600 square kilometers. The tragedy claimed dozens of lives, destroyed thousands of homes, submerged valuable biotopes, and endangered or killed wildlife, including animals in a nearby Zoo. It is hard to imagine a more devastating event in Europe in recent decades.

Within the Showcase Ukraine, it wasn’t just a simple relocation and re-presentation of the exhibition about the Kakhovka Reservoir. According to Tamara, it was adapted and reshaped specifically for the Georgian audience. The focus was placed especially on the history of the reservoir, its construction, and its recent destruction.

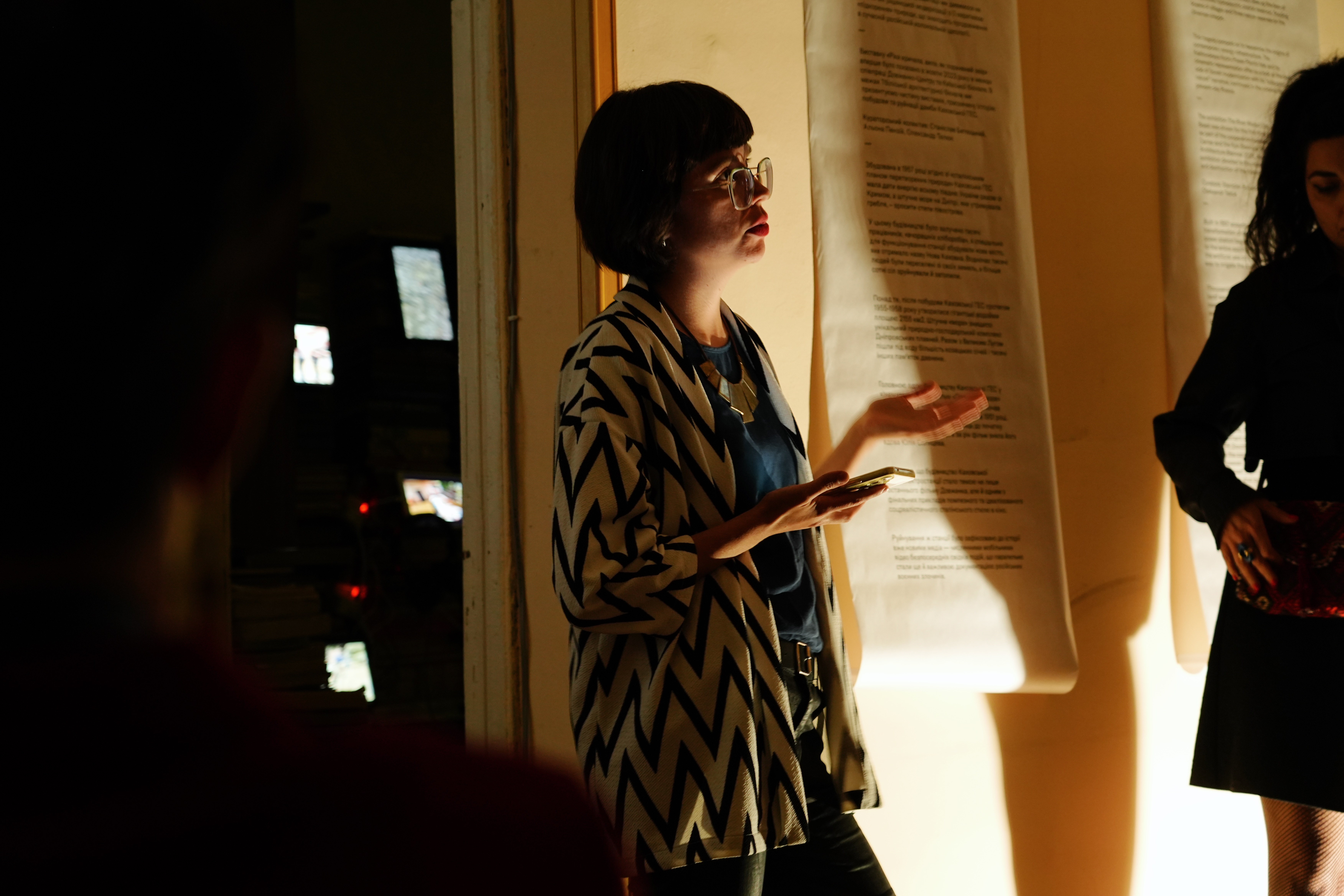

On the subject of the dam, the Showcase also featured a screening of Ivan Kavaleridze's 1991 film Stormy Nights (Shturmovye nochi), which was attended by one of the project's curators, Alona Penzi, a film critic and director of the archives at The Oleksandr Dovzhenko National Centre, which Tamara said was very enriching: “We had an opportunity to make tours through the exhibition, explaining how the materials were gathered, the concept and so on. She had an opportunity to address another audience as well, and she told us the story behind this, because it was a documentary feature film documenting Soviet construction of these infrastructural projects, how they were conceived. They were used as propaganda. It wasn’t interesting just from the architectural point of view, but also as this dissemination of information on soviet projects was taking place.”

The exhibition The River Wailed Like a Wounded Beast was situated at the very heart of the Biennale, with a large part of it housed in the historic — but still functioning — Hydrometeorological Institute. Alongside the visitors, scenes from the construction of the Kahkovka Dam became a common backdrop for the institute's staff for several weeks. According to Tamara, they were amazingly tolerant and eventually enthusiastic about the whole event: “I saw on different occasions that the director or an elderly person from the staff brought their friends and family members and they were super proud to show them around and to explain the project because our exhibition and screening they were the central part of it. It was very nice to see how much pride they took that we had this very interesting footage, and how they explained that all this came from Ukraine and from there, and it’s based on this cooperation. It was very touching.”

The theme of the exhibition resonated strongly with the younger audience. Tamara enthusiastically recalls that the film screening sold out almost immediately: “People took a lot of interest in something very urgent and something that comes from a friendly state for which we have a lot of solidarity as well.” For Tamara, the fate of Ukraine is a very sensitive topic. She is determined to keep reminding people about the war, because, as she says, three years is a long time, long enough for people to start getting used to it — and that, in her view, must not be allowed to happen.

That’s exactly why, when the opportunity arose during the Biennial’s preparations to collaborate with Ukrainian organizations and draw attention to what Ukraine is going through, she didn’t hesitate for a moment, especially since she already knew MetaLab and Kultura Medialna quite well.

Memory, grief, trauma, and the concrete that binds it all together

“Our cooperation goes back to 2018, when we started working together as part of a Creative Europe project. Anna was there from the beginning, and Kultura Medialna joined a little later,” Tamara recalls the beginnings of their joint international projects, and Anna from MetaLab complements her: “MetaLab and Tbilisi Architecture Biennial already had a long-term collaboration, although this is the first time we officially worked together under the MetaLab name. Before, our colleagues participated through different organizations—for example, me with MistoDiya. We also had a joint project in Ivano-Frankivsk. So, it's really been an ongoing collaboration and friendship over the years.”

The determination to undertake another project, despite Anne's good experience, was not easy to find at first. The MetaLab team has been swamped with work, which has been linked to the omnipresent war for the last few years. “MetaLab calls itself an urban laboratory, but I think we need to rethink that formulation. Over the last three years, our focus has shifted—we are still a laboratory, still make tests and experiment with different methods, but we’ve also gained new perspectives along the way,” Anna begins her story.

“Originally, our main goal was to help cities improve their infrastructure using democratic, participatory methods and various cultural activities with citizens,” Anna continues. Initially, MetaLab created a makerspace, now called POLE, where the aim was to integrate traditional crafts and modern technologies. It transformed into a centre for research and product design, and it became a space for experimentation with special regard to engaging local residents and supporting circular economies.

Their working reality changed when Russia launched its full-scale invasion of Ukraine, and thousands of people fleeing the war began arriving in the western part of the country. Very quickly, MetaLab turned its focus to converting any available spaces into livable ones. This marked the beginning of their current project, Co-Haty, which responds to the acute housing crisis.

According to Anna, the decision to take on another project, especially an international one, wasn’t an obvious choice for the already busy MetaLab. “But we wanted to support the project and to join it, as we saw the importance of being there, especially in Tbilisi, to give voice to Ukrainian projects. Given the current situation, participation in this kind of international forum is also a form of diplomacy,” explains their position Anna.

The project, presented by MetaLab as part of Showcase Ukraine, stems as much from their determination to recycle whatever can be recycled as it does from the need to rebuild what war has destroyed. “Our team regularly travels to the territories in eastern and southern parts of Ukraine to assist with housing there. We’ve started collecting rubble and testing techniques we can use further,” Anna explains how they started their experiments with building materials that could help to make use of at least some of the enormous amount of rubble they have to deal with (sooner or later) in Ukraine.

The method of creating concrete from existing material is not new, and MetaLab began experimenting with it in 2023. “We know that concrete is the most polluting material to be produced, and we understand that we cannot rebuild Ukraine without it, but we were trying to find an alternative,” explains Anna. “That’s how we found this ancient technique, and it’s used in different historical buildings and constructions in Ukraine.”

The technique of reusing old bricks or other previously used construction materials dates back to ancient Rome. Rubble becomes the base for new concrete. According to Anna, the process of making it takes longer, but what makes it remarkable is that it requires few raw materials, no heat, and over time, it becomes more durable than the original material.

They presented their concept at the Tbilisi Architecture Biennial through the exhibition The (Un)Seen Lands, which approaches the otherwise pragmatic topic of building materials in a surprisingly poetic way. The destruction of thousands of homes, the forced displacement of residents, injuries or deaths caused by war - all of this brings grief, and that grief does not simply disappear. It must be worked through.

“The psychologists recommends that, to accept and to acknowledge it,”Anna explains the ideas that shaped MetaLab's contribution. Recycled rubble can bring a dimension to new buildings and life in them other than just a fresh start. “I can imagine that for many people, they would prefer to have something new because everything reminds them of everything they went through, which is also okay. But there is also a question if it’s healthy, if it's okay to do it like this. It’s still important to have something that will remind you of those parts of your life.”

In this context, Anna vividly recalls a visit to Sarajevo, a city that endured years of siege during the war in Bosnia and Herzegovina. Even today, you can find buildings bearing visible marks of fighting and shelling. She asked the locals why they hadn’t repaired them. Their answer was powerful and deeply thought-provoking: “People don’t just want to scratch it out, to erase it, it’s part of their lives. They learn to live with that, and it’s part of commemoration and a reminder that it can happen again.”

MetaLab is therefore working to refine the technology for creating new material from the old - from destroyed homes and buildings - that carry not only sorrow, but also the memory of a nation that should not simply forget, but rather seek ways to come to terms with the war.

The phrase embodying their intention, “Grief doesn’t vanish”, became the central idea behind MetaLab’s artistic presentation at the Biennial. The author of the concept is Anna’s colleague Yuliia Holiuk, who took part in the summer school Researching Common Territories, co-organized by the Tbilisi Architecture Biennial. “These ideas came from her discussions with some participants originally from occupied territories in Georgia, and they also had this experience of fleeing their houses. So this idea appeared through their personal experience discussions with Yuliia,” tells Anna.

Tamara and Anna agree that the Showcase Ukraine reveals how much Ukraine and Georgia share in their not-so-distant past: forced displacement of people, ecological disasters, Russian occupation. These are all traumas whose artistic representation, with all its layers, can help in processing them.

The combination of practical and artistic perspectives on architecture seems to be a hallmark of the Tbilisi Architecture Biennial. In this context, Tamara recalls their very first edition of the Biennial in 2018, which carried the subtitle The Buildings are not Enough. “Architecture doesn’t really exist as only architecture, it’s about the people who live there, their lives. Life isn’t only based on walls, there is a lot of culture coming in,” Tamara shares her thoughts. “This part produced by MetaLab about the rubble, it wasn’t about the pure presentation of the things, but it was presented in a very artistic way in the shape of installations, much more impressive and more understandable for the people.”

Such a normal life, full of battles

Although Tamara and Anna both speak highly of their collaboration on the Showcase Ukraine, its preparation was not the easiest one. Tamara explains that it was only through this project that she fully grasped the situation Ukrainians are in, and began to see in a new light the determination and effort they had to invest to make it happen.

At the time of our conversation (March 2025), Tbilisi had just come through a long and turbulent period marked by protests. Since October 2024, when the results of Georgia’s parliamentary elections were announced, citizens have taken to the streets almost regularly—not only to protest what they view as rigged outcomes, but also to oppose the country’s shift away from European integration.

In the context of daily protests, often targeted by police and violent groups associated with the ruling party, Tamara now values MetaLab’s and Kultura Medialna’s participation in the joint project even more. “In our case, there are some people who are occupied with the protests all day, they go to the court hearings, this and that; I on my own can be there every day after 6 o'clock for three, four hours. It also brings a lot of guilt if you have no time to do that, because some people are in prison, etc. They rely on your support. But in case of Ukraine, it is not scheduled, like: ‘I will go to war after 6 o'clock.’ It can happen any time if there are attacks.”

During the preparations for the Ukrainian showcase, Tamara began to feel a deep sense of reverence when she had to discuss seemingly banal matters, like schedules and project management, with Ukrainian partners whose everyday lives were, to varying degrees, shaped by the struggle for their country and for survival.“But they are still there, and they are still deciding to dedicate their time to continue not as usual, but as normally as possible, which is absolutely insane. This is where I see their courage and their dedication also, because if the country stops now it will be very difficult to catch up with things later, and somehow people in Ukraine really do it on a daily basis,” Tamara says with wonder in her voice.

Anna emphasizes that international projects like this one offer a chance to step outside of their current situation – if not physically, then at least mentally – and to realize that what they are living through now is far from normal. “We don’t want to adapt, we want to stop it and live a normal life. All these international collaborations and projects, they are allowing us to talk about this and to look a bit from the side on what’s going on, and also to take a break from it.”

For the Ukrainian partners, war brings daily compromises. Beyond practical concerns, such as access to housing, electricity, internet, and of course, safety, it has also affected other areas of life.

MetaLab, for example, has always been an organisation led entirely by women, but it also focused on activities that only women can participate in for some time now. Given their focus on urban development, housing, and design, this team composition presents a considerable challenge—they simply lack the male workforce needed to implement many of their projects.

However, this is just a minor inconvenience that they will ultimately overcome. “We face burnouts and depression and difficult mental safety. That’s why it’s very challenging to do any project that is not practical,” Anna explains the situation they are in. After our conversation, she will have a lot of work ahead of her, such as finding and renovating housing for fifty internally displaced people. But she adds that they equally feel the need not to give up and to draw attention to their situation in the international environment.

In their project The (Un)Seen Lands, MetaLab also reflected on how to maintain a connection to the land and regions of the country that are being occupied by Russia. Anna does not hide the fact that skepticism often sneaks into their thoughts. “We still use this terminology like post-war reconstruction, but it’s still hard to accept this war, we cannot see the post-war. We see the war. We appreciate the people who have the ability and capacity to think about that, but we are still in the current state of the country in war,” Anna says with a tired sigh.

But there are things that bring her joy, and the Showcase Ukraine is definitely one of them. For her team at MetaLab, it brought, for example, spontaneous conversations and discussions with the visitors of the Biennale, which are incredibly valuable. “I believe in talks, you can always find the opportunity to share knowledge and experience and to gain understanding,” Anna enthuses, immediately adding that from one such informal and unplanned discussion, a connection was made that she is very happy about. In Georgia, they found someone who would love to help them with their developmental and research activities in Ivano-Frankivsk, and with humor, she adds that a man who is not at risk of mobilization is exceptionally useful to them.

Tamara is still excited about the collaboration and its results: “For me it was all a great experience because we reconnected on a more active level with Anna and Katya [from Kultura Medialna] and this was really good, working on something together. But also the response from the audience, how seriously they took the project.”

Why wouldn't they take the project seriously? As Tamara noted during the interview, nature doesn't stop at borders — it spills over. The same goes for war and its effects, which ripple through every European country.

Authors: Petra K. Adamková

ZMINA: Rebuilding is a project co-funded by the EU Creative Europe Programme under a dedicated call for proposals to support Ukrainian displaced people and the Ukrainian Cultural and Creative Sectors. The project is a cooperation between IZOLYATSIA (UA), Trans Europe Halles (SE) and Malý Berlín (SK).