About the project

Director Kornii Hrytsyuk — about the «Eurodonbas» film:

In the fall of 2023, my documentary «Eurodonbas» will hit theaters across Ukraine. After more than a year of screenings abroad, from Canada to Scotland, the film will finally reach its most important audience — Ukrainians. Before this release, we had just one public screening in Ukraine — back in October 2022 in Kyiv, during the «Kharkiv Meet Docs» film festival.

For film projects, a theatrical release is both an ending and a new beginning. This kind of distribution usually happens after festivals and other special screenings. The film “goes to the people,” and our work on it comes to a close. So far, «Eurodonbas» has been my longest project. We began working on it in 2019. Nearly all of 2020 was spent in development and searching for funding. In 2021, we finally shot the film and completed post-production. Distribution was planned for the spring of 2022, but then came February 24th...

When my producer and co-writer, Anna Palenchuk, and I first conceived «Eurodonbas», our main goal was to tell the story of the region's modernization through a Western lens, specifically for a Ukrainian audience. We weren’t thinking about festivals or foreign viewers, and we were determined not to create «yet another bleak arthouse film about Donbas for export». Instead, we decided to make a vibrant documentary that would inspire audiences to fall in love with the European heritage of Eastern Ukraine.

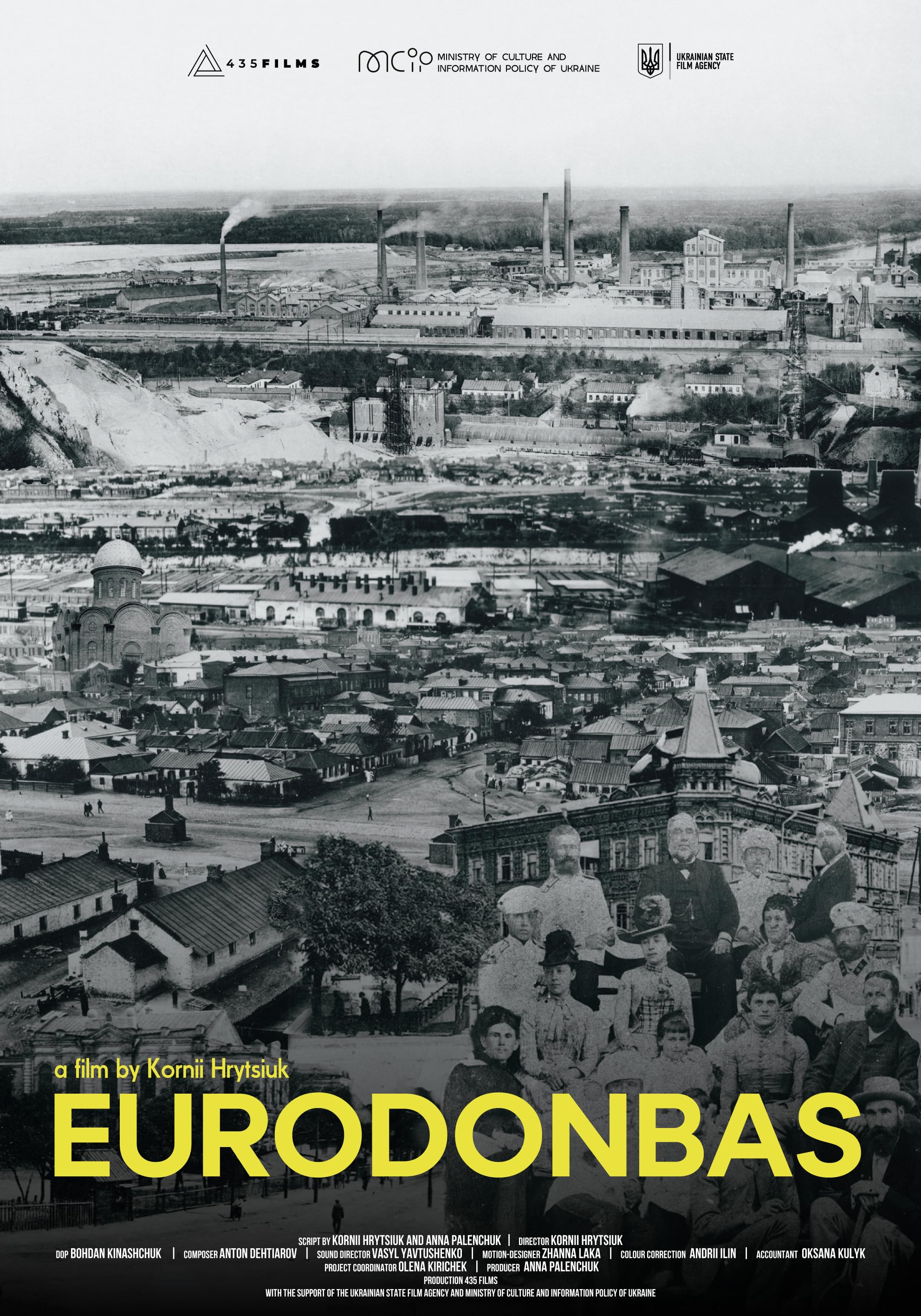

To bring this vision to life, we relied on unique locations, charismatic characters, and 19th-century archival materials that had never been seen in Ukraine. Moreover, we decided to «bring these archives to life» making them look like actual footage from the past. Of course, we could only achieve this with funding from the Ukrainian State Film Agency. Thanks to our imagination and the talent of our video designer Zhanna, we made it happen.

And this isn't just my opinion — over the past year, we've screened our film in many countries. Due to the war, we've received and continue to receive numerous requests to show «Eurodonbas» abroad, at various venues, including film festivals we hadn’t even considered.

In our view, this film is entirely Ukrainian, yet it was shown to great enthusiasm at prestigious events like «Hot Docs» in Toronto, one of the top five documentary film festivals in the world. At one of the screenings in Canada, we heard a comment from a viewer that inspired the title of this text.

Our film indeed features many rare archives from Donbas at the turn of the 19th and 20th centuries. We searched for and found them wherever we could — in a Belgian chemical corporation, Welsh museums, family collections in France, and German religious communities. However, the full-scale war has also turned our footage into a unique archive of its own today.

During our film expedition in the spring and summer of 2021, we traveled countless kilometers, from the shores of the Sea of Azov to Lysychansk. Nearly all the places we visited have since either become frontlines, been destroyed, or are now occupied. It turns out that our project was one of the last major Ukrainian films (not in terms of achievements — I'm not likely to say that about my own work — but in terms of scale) shot in Donbas before the full-scale war.

The region we filmed no longer exists as it was. Maybe it will become better after our victory. Or perhaps the war will turn it into a place where no one will want to live. But one thing is certain — it will never be the same as it was in 2021. And while I’m not a historian or a philosopher, just a filmmaker from Donetsk, I believe this war is closing a certain historical chapter right before our eyes.

About 130-150 years ago, thanks to Western investments and visionary industrialists like John Hughes, Donetsk and Luhansk (previously agricultural and sparsely populated Ukrainian regions) transformed into industrial and cosmopolitan hubs. The processes that began during that time — labor migration, the establishment of large enterprises, and urbanization driven by rural depopulation—continued throughout the Soviet era. These developments shaped Donbas into what we know today.

Entering the post-industrial 21st century, Donbas carried with it a powerful but outdated legacy that the state still attempted to support through modernization subsidies, privatization, and other methods, all while hesitating to implement radical reforms that could provoke social unrest. Had it not been for 2014, this situation might have continued to the present day: Donbas, which once seemed to «feed everyone», would have remained a backward burden, clinging to nostalgia for its past.

This great war, with its catastrophic destruction — even of giants like Azovstal and the Ilyich Iron and Steel Works — seems to definitively close the industrial chapter in Donbas's history. Most of its enterprises will likely be impossible to restore. Moreover, there is little economic or social rationale for doing so. For Donbas to have a future, it must finally become history, along with its massive factories, industrial complexes, and Russian encroachments. This is the only chance for Ukrainian Luhansk and Donetsk to thrive and to create new meanings for themselves.

And it is in this that I personally find some optimism during these challenging times. While working on this project with Izolyatsia, it was incredibly difficult to review both our footage and the archival materials we found. I had to confront the reality that places like Mariupol no longer exist. The same goes for Lysychansk, Bakhmut, and many other cities and towns.

During our interview for the film, historian Larysa Yakubova intriguingly referred to the European Donbas that was lost in the tumultuous events of the early 20th century as «Atlantis». Its remnants, along with the post-Soviet Donbas, are permanently captured in our «Eurodonbas» film. The film, «crafted from a multitude of archives, has now itself become an archive».

Don't miss: